Look here for the syllabus and more information.

You can also have a look at a previous semester's (2005) web site of mine for the same course.

Main lectures: MWF 14:05 - 14:55, in Skiles 202.

My office hours are: Thu 10-12 in my office (Skiles 133).

You're also welcome to ask me questions any time you see me, anywhere.

Recitation sessions: TTh 14:05-14:55 in Skiles 202 (instructor Daniel Tiefa)

Dan's office hours are TBA.

There will be quizzes each Thursday (except for the first one) for the last 15 minutes of the session. One problem will be asked among those (or very much resembling one of those) that were assigned as homework.

The quizzes are worth 20% of the grade (the two smallest quiz scores will be discounted for each of you), each of the two midterms (Feb 9 and March 14) is worth another 20% and the final is worth 40%.

We covered §13.1.

We saw examples of functions of a real variable whose values are 2D or 3D vectors.

We defined the limit

HW problems: §13.1: 1, 2, 15, 16, 21, 22, 27, 28, 39, 41.

For the first week only, my office hours will be held on Friday, 3-5.

We saw how to compute the derivatives of vector valued functions which have been

made by piecing together, in various ways, other functions. For example, we saw that

if ![]() is a scalar function and

is a scalar function and ![]() is a vector function then the derivative

of the function

is a vector function then the derivative

of the function ![]() which is defined by

which is defined by

HW problems: §13.2: 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 17, 18, 21, 22, 27, 29, 32.

The first midterm exam will take place on Fri, Feb 9, during our regular meeting and in the same place.

The second midterm will take place on Wed, Mar 14, also during our regular meeting and in the same place.

We saw a few examples of vector-valued functions viewed as parametrizations of

curves in space. We saw that when ![]() traverses a curve

traverses a curve ![]() then

then

![]() is a tangent vector

of

is a tangent vector

of ![]() at point

at point ![]() , and solved some problems which

asked geometric questions about curves that had been described in parametric

form.

We also saw how to find the intersection points of two curves that have

been given to us in parametrized form. One must be careful in this problem not

to use the same name of the parameter for both curves.

, and solved some problems which

asked geometric questions about curves that had been described in parametric

form.

We also saw how to find the intersection points of two curves that have

been given to us in parametrized form. One must be careful in this problem not

to use the same name of the parameter for both curves.

Some of the problems listed below you cannot solve without reading the rest of §13.3 (we will cover this on Wednesday).

HW problems: §13.3: 1-4, 9, 14, 15, 18, 35-38.

We finished §13.3: talked about the unit tangent vector ![]() to a curve at point

to a curve at point ![]() and the principal normal vector

and the principal normal vector ![]() as well as the osculating plane they define. We computed

an example.

as well as the osculating plane they define. We computed

an example.

Then we saw how to calculate the length of a curve parametrized by the vector function ![]() ,

for

,

for ![]() . We computed some examples and also saw by example that the formula we gave

for arc-length does not depend on the parametrization of the curve. That is we took two different

paraetrizations of a specific curve (a circle, actually) and used our length formula with

both of these parametrizations and we got the same result, as we should.

. We computed some examples and also saw by example that the formula we gave

for arc-length does not depend on the parametrization of the curve. That is we took two different

paraetrizations of a specific curve (a circle, actually) and used our length formula with

both of these parametrizations and we got the same result, as we should.

HW problems: §13.4: 1-4, 8, 9, 17, 23.

My office hours tommorrow, Thursday Jan 18, will be held from 9-11 (not 10-12) as I want to go to a lecture at 11 (this change may become permanent).

If any of your planned to see me from 11-12, please send me a message to set up an appointment (but not on Thursday).

We covered the part of §13.5 that concerns plane curves and their curvature. We saw how to

reparametrize a curve which has been given to us in parametric form ![]() in such a way that

the parameter is now

in such a way that

the parameter is now ![]() the arc-length along the curve. This parametrization has the property,

which characterizes it, that the velocity vector has constant magnitude equal to

the arc-length along the curve. This parametrization has the property,

which characterizes it, that the velocity vector has constant magnitude equal to ![]() .

The curvature of a plane curve is defined as the derivative with respect to

.

The curvature of a plane curve is defined as the derivative with respect to ![]() of the angle formed

by the tangent line to the curve and the

of the angle formed

by the tangent line to the curve and the ![]() -axis, in absolute value. (This definition will have to

be amended next time in order to define the curvature of space curves.) We then saw formulas

that allow us to calculate the curvature given the parametrization of the curve. We applied these

formulas to several examples. Finally we defined the radius of curvature and the center of curvature.

-axis, in absolute value. (This definition will have to

be amended next time in order to define the curvature of space curves.) We then saw formulas

that allow us to calculate the curvature given the parametrization of the curve. We applied these

formulas to several examples. Finally we defined the radius of curvature and the center of curvature.

Of the following problems, do now those that concern plane curves, and leave those about space curves for after having finished §13.5.

HW Problems: §13.5: 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 13, 14, 21, 22, 41, 42, 58.

We saw how one defines the curvature ![]() of space curves (curves which are not known

to be contained in a plane) and computed some examples.

of space curves (curves which are not known

to be contained in a plane) and computed some examples.

We also saw that acceleration of a particle moving along a curve ![]() , that is

the vector

, that is

the vector

Do the problems of §13.5, listed above, which you could not do before today's lecture.

We covered §13.6. We saw how to apply some of the things we've seen so far to problems of Mechanics (motion of particles under certain forces). In particular, we proved Kepler's 2nd law which states that if a particle is moving under the influence of central force (force parallel to the location vector) then its location vector sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

We did not have time to cover the subsection on initial value problems. Please go over Examples 3 and 4 on p. 809 and 810.

HW Problems: §13.6: 1-4, 8, 9, 11, 14, 15.

We talked a little about how to solve initial value problems of the second order such as those that arise from Newton's equation in kinematics (read §13.6).

Then we moved on to §14.1 and talked about real-valued functions of two or three variables

HW Problems: §14.1: 1-10, 35, 37, 39.

We first remembered what kind of curves in the plane have an equation ![]() which is

a polynomial in

which is

a polynomial in ![]() and

and ![]() of degree at most

of degree at most ![]() , a quadratic equation. These are the so-called

conic sections: ellipse, hyperbola, parabola, straight line, a pair of straight lines or

a single point. Next we wrote down the general quadratic equation in three variables

, a quadratic equation. These are the so-called

conic sections: ellipse, hyperbola, parabola, straight line, a pair of straight lines or

a single point. Next we wrote down the general quadratic equation in three variables ![]() , that is

an arbitrary polynomial in these variables whose degree is at most

, that is

an arbitrary polynomial in these variables whose degree is at most ![]() . The case now are many more

and I am not asking that you memorize the entire list in your book (§14.2) but that you learn,

as we did in class, how to figure out the shape of a given surface, whose equation you're given, by

cleverly fixing some of the variable to appropriate values (in your book these are called intercepts

and traces), and also by taking advantage of the symmetries of the equation. Do learn the few examples

we did in class.

. The case now are many more

and I am not asking that you memorize the entire list in your book (§14.2) but that you learn,

as we did in class, how to figure out the shape of a given surface, whose equation you're given, by

cleverly fixing some of the variable to appropriate values (in your book these are called intercepts

and traces), and also by taking advantage of the symmetries of the equation. Do learn the few examples

we did in class.

HW Problems: §14.2: 2, 4, 10, 12, 20, 22, 26, 40, 43.

A student note taker is needed in this course to take notes for a student with a disability. The note taker will be paid a stipend for this assignment. Skills needed are the ability to take accurate, legible, and organized notes and a commitment to attend every lecture. If interested, please contact Tina Allen via office phone at 404-894-2563 or via email at notetaker@vpss.gatech.edu as soon as possible. Be sure to indicate the Professor's name, time, day and course number/ section in the subject line of the announcement.

We saw how to present geometric information about a function ![]() or

or ![]() (or its

graph, representable by the equation

(or its

graph, representable by the equation ![]() or

or ![]() ) by drawing its level curves

for two-variable functions, i.e. the curves whose equation is given by

) by drawing its level curves

for two-variable functions, i.e. the curves whose equation is given by ![]() for

various values of

for

various values of ![]() , or its level surfaces (three-variable case) which are the surfaces

representable by the equation

, or its level surfaces (three-variable case) which are the surfaces

representable by the equation

![]() , again for various values of

, again for various values of ![]() .

.

HW Problems: §14.3: 4, 5, 8, 14, 19, 20, 21, 25, 28.

Next we saw how one defines the partial derivatives (with respect to each of the variables) of functions of more than one variable, and saw how to compute some examples by treating all variables but the one we're differentiating with as constants.

My apologies to those of you (if any) who came to my office hours Thursday. I entirely forgot.

I will be in my office from 4-5 tomorrow Friday.

Mihalis

We finished §14.4, by giving more examples of how to compute the partial derivatives

of functions of several variables and by talking about the geometric significance of

the partial derivatives of a function ![]() .

.

HW Problems: §14.4: 1-10, 23, 41, 53.

We then started speaking about §14.5. We defined the ![]() -neighborhood (and deleted neighborhood)

of a point

-neighborhood (and deleted neighborhood)

of a point

![]() , where

, where ![]() . We also defined the concept

of an open set

. We also defined the concept

of an open set

![]() and saw, as an example, that the upper half plane

and saw, as an example, that the upper half plane

![]() :

:

You can find a practice exam (for 50 min) here in PDF.

We defined what closed sets are (the complements of open) sets as well as what the interior points of a set are and its boundary points. We saw several examples, both in dimension 2 as well as in dimension 1.

HW Problems: §14.5: 1-20.

For the first test (this Friday, in class) you are expected to know all that has been taught to you by today (Monday). Please come early so as to start on 14:05 sharp.

There will be a quiz on Thursday as usual.

We went over the practice exam and aswered some questions.

We had our first test. Here are the problems.

Solution:

Velocity:

![]() .

.

Speed:

![]() .

.

Force:

![]() .

.

Solution:

(a)

![]() .

.

(b) For a vector to be parallel to the ![]() -plane means that its

-plane means that its ![]() -coordinate is

-coordinate is ![]() . This

happens for the first time at

. This

happens for the first time at ![]() . At that moment the velocity

vector is

. At that moment the velocity

vector is

![]() . A parametrization of the tangent line (which goes through

the point

. A parametrization of the tangent line (which goes through

the point

![]() and has the direction of the vector

and has the direction of the vector ![]() is

is

Solution:

(a) The argument of the function ![]() must be positive, hence the domain is

must be positive, hence the domain is

Solution:

(a) This is the region where ![]() and

and ![]() have the same sign or some of them is zero. This is the

first and third quadrant of the plane, together with the

have the same sign or some of them is zero. This is the

first and third quadrant of the plane, together with the ![]() - and

- and ![]() -axes.

-axes.

Any point of that set which is not on the axes is an interior point as one can draw a disk centered at it which is entirely in the set. Any point on the axes is not an interior point as any disk around such a point will contain points outside the first and third quadrant.

For this reason all points of the axes are boundary points. There are no other boundary points as any point

inside a quadrant and not on an axis will have a small disk around it which contains either only points of

the set or of its complement and not from both.

(b) The only difference of this shape from that of (a) is that the ![]() - and

- and ![]() -axes are not part of

the set now. However the set of interior points and the set of the boundary points remains the same

as that of (a). (In this case the set of boundary points, namely the two axes, is not part of the set itself.)

-axes are not part of

the set now. However the set of interior points and the set of the boundary points remains the same

as that of (a). (In this case the set of boundary points, namely the two axes, is not part of the set itself.)

We defined formally what the limit of a two-variable function is when

![]() ,

and when a function is continuous at a point

,

and when a function is continuous at a point ![]() .

We calculated the limits using the definition for some very simple functions.

.

We calculated the limits using the definition for some very simple functions.

We also saw examples of functions of two variables which exhibit strange behaviour, by one variable standards. For example we saw a function which is everywhere continuous with respect to each of the variables and has everywhere partial derivatives, yet is not continuous at (0,0).

HW Problems: §14.6: 1-5, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27.

You can find your grade here in PDF.

We defined what it means for a function of many variables to be differentiable at a point ![]() ,and also defined the gradient of a differentiable function

,and also defined the gradient of a differentiable function ![]() at

at ![]() , as the only

vector

, as the only

vector ![]() that makes the following true:

that makes the following true:

See, for example, this page for the big-O and little-o notation that we talked about today.

HW Problems §15.1: 12-16, 33-37, 39, 40.

We talked about the concept of directional derivatives and how to compute them using the gradient of a function. Also saw that the direction of the gradient is the direction of maximum rate of increase of a function. Saw several examples.

HW Problems §15.2: 11-14, 23-26, 40, 41.

We went over the Mean Value Theorem for scalar functions of one variable, and used it to prove the mean value theorem for scalar functions of a vector variable. We remarked that the Mean Value Theorem is not true for vector valued functions. We saw some consequences of the MVT: if two functions have the same gradient in a connected open set then they differ by a constant.

Next we reviewed the chain rule for functions of one variable and saw the form it takes for the composition of a scalar function of a vector variable with a vector valued function of one variable. We saw how to construct the dependency diagram when we have many quantities that depend on others, and use it to derive the appropriate chain rule.

Please read from §15.3 about implicit differentiation.

HW Problems §15.3: 1, 3, 4, 6-8, 17, 18, 25, 27, 29, 30, 36, 58.

We pointed out that

![]() is a normal vector to the curve (or surface)

is a normal vector to the curve (or surface)

![]() ,

, ![]() a constant. We used this to compute normal and tangent vectors

to curves and surfaces amd also angles between curves and surfaces. These angles

are defined to be the corresponding angles between their tangent objects at

the intersection. For example, if we are seeking the angle between a curve and a surface

which intersect at a point

a constant. We used this to compute normal and tangent vectors

to curves and surfaces amd also angles between curves and surfaces. These angles

are defined to be the corresponding angles between their tangent objects at

the intersection. For example, if we are seeking the angle between a curve and a surface

which intersect at a point ![]() we must measure the angle between a tangent vector of the curve at

we must measure the angle between a tangent vector of the curve at ![]() and the

tangent plane to the surface at

and the

tangent plane to the surface at ![]() . This is most easily measured by first finding

the angle between the tangent to the curve and the normal to the tangent plane, and then

subtracting that angle from

. This is most easily measured by first finding

the angle between the tangent to the curve and the normal to the tangent plane, and then

subtracting that angle from ![]() .

.

HW Problems §15.4: 1, 2, 10, 11, 19, 20, 26, 27, 28, 34, 36.

We saw what is the analogue in two variables of the criteria, involving first and second derivatives, that we know for deciding where a function's local maxima and minima are. The first stage of the method is to locate the points where the function's gradient vanishes. Each of those points is then checked using higher order partial derivatives of the function at that point in order to decide if there is a local extremum at that point or if it is a saddle point.

HW Problems §15.5: 1, 2, 5-8, 25, 26.

We saw how to find the (global) minima or maxima of a function of two variables defined in a closed and bounded domain. We have to find the critical points in the interior of the domain and then parametrize our boundary, which gives rise to a function of one variable corresponding to our function being evaluated on the boundary. This one-variable function we extremize (find its extrema) separately. The extrema of this one-variable function along with the critical points in the interior are then compared in the value of the function at them to find the global extrema.

HW Problems §15.6: 1-6, 19-22, 27.

We talked about the problem of finding the minimum or maximum of a function ![]() when

when

![]() is not free to take any values in the domain of definition of

is not free to take any values in the domain of definition of ![]() but it has to satisfy

some condition, which is usually given in the form

but it has to satisfy

some condition, which is usually given in the form ![]() .

Sometimes one can solve

.

Sometimes one can solve ![]() for one of the variables in

for one of the variables in ![]() and substitute the

resulting expression in

and substitute the

resulting expression in ![]() thus getting a problem of ordinary function extremization

without side conditions and in one variable less. We saw two such examples but this

method is most often inapplicable as it is not easy to solve

thus getting a problem of ordinary function extremization

without side conditions and in one variable less. We saw two such examples but this

method is most often inapplicable as it is not easy to solve ![]() for one of the variables,especially if

for one of the variables,especially if ![]() is a three-component vector and

is a three-component vector and ![]() is non-linear.

Even if possible the resulting expression for

is non-linear.

Even if possible the resulting expression for ![]() may be too complicated to work with.

may be too complicated to work with.

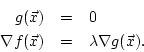

We then saw the method of Lagrange (or Lagrange multipliers as it is commonly known),

which allows one to solve the above problem by solving a, generally non-linear,

system of equations in the unknowns ![]() and

and ![]() , the latter being a auxiliary

variable which is not used except to help find the values of

, the latter being a auxiliary

variable which is not used except to help find the values of ![]() .

The system of equations is

.

The system of equations is

HW Problems §15.7: 1-4, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21, 23.

We gave some more examples of the method of Lagrange multipliers and saw how it applies to the case of a function of three variable subject to two conditions.

We also saw that there is a way to avoid introducing the Lagrange multiplier (the ![]() variable, which we throw away after solving the system of equations). This can

be done by checking the parallelism between the two fectors

variable, which we throw away after solving the system of equations). This can

be done by checking the parallelism between the two fectors ![]() and

and

![]() (the gradients of the function to be optimized and the constraint function) by checking the

equation

(the gradients of the function to be optimized and the constraint function) by checking the

equation

The answer is that the vector equation

![]() is really only two

equations. If one writes it out (using the determinant form) one notices immediately

that any of the resulting three equations can be obtained from the other two, so one can throw

away any one of them (but only one) without changing the solutions to our system.

Now it is clear that we have three equations in three unknowns.

is really only two

equations. If one writes it out (using the determinant form) one notices immediately

that any of the resulting three equations can be obtained from the other two, so one can throw

away any one of them (but only one) without changing the solutions to our system.

Now it is clear that we have three equations in three unknowns.

We saw how to use the summation sign and iterated (multiple) summation sign via several examples. We also evaluated several simple sums.

HW Problems §16.1: 1-4, 13-17.

You can find a practice exam (for the 50 min 2nd midterm) here in PDF.

Note Taker Announcement:

A student note taker is needed in this course to take notes for a student with a disability. The note taker will be paid a stipend for this assignment. Skills needed are the ability to take accurate, legible, and organized notes and a commitment to attend every lecture. If interested, please contact Christina Bibbs at notetaker@vpss.gatech.edu, and be sure to indicate the Professors name, time, day and course number in the subject line of your email. Thank you so much for your willingness to assist our office in this process. Please contact our office if we can be of any assistance.

We defined the integral of a function ![]() over a rectangle

over a rectangle ![]() via

lower and upper sums corresponding to partitions of

via

lower and upper sums corresponding to partitions of ![]() . We

evaluated, using the definition, only some simple integrals.

. We

evaluated, using the definition, only some simple integrals.

HW Problems §16.2: 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, 11.

We stated the Mean Value Theorem for double integrals over connected domains (§16.2).

When a domain is such that all its intersections with lines parallel to the ![]() -axis are intervals,

and the set of

-axis are intervals,

and the set of ![]() -values used in the domain consititute an interval the domain is called of Type I

(and of Type II if the same properties hold with

-values used in the domain consititute an interval the domain is called of Type I

(and of Type II if the same properties hold with ![]() and

and ![]() reversed). For such a domain

we saw how to evaluate a double integral of a function as a single integral whose function to be integrated

is an integral itself.

reversed). For such a domain

we saw how to evaluate a double integral of a function as a single integral whose function to be integrated

is an integral itself.

HW Pproblems §16.3: 1-6, 13, 14, 33, 34, 43, 46.

We did not cover any new material. Instead we went over the practice exam, in preparation for Wednesday's exam.

We had our second test. Here are the problems:

Solution:

Suppose the vertex of the box lying in the first octant has coordinates ![]() , with

, with

![]() . It follows that the volume of the box is

. It follows that the volume of the box is

Solution: We have

Solution:

The surface is a level surface of the function

Your formula for ![]() may not involve partial derivatives of

may not involve partial derivatives of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

Solution:

We have

![]() and

and

![]() .

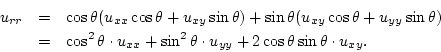

By the chain rule we get

.

By the chain rule we get

You may find them here in PDF.

We went through the problems that were on the last test and their solutions.

We saw how to evaluate a double integral using polar coordinates. The first task is to find

the domain ![]() in the

in the ![]() -plane which corresponds to the given domain

-plane which corresponds to the given domain

![]() (in the

(in the ![]() -plane). For example, if

-plane). For example, if ![]() is the unit disk in the cartesian plane

(the

is the unit disk in the cartesian plane

(the ![]() -plane) then

-plane) then ![]() is a rectangle in the

is a rectangle in the ![]() -plane defined by

-plane defined by

Please read by yourselves the evaluation of

![]() from the

end of §16.4. This is a very important integral in all mathematics and especially its applications

to science and engineering.

from the

end of §16.4. This is a very important integral in all mathematics and especially its applications

to science and engineering.

HW Problems §16.4: 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 17-20, 23, 24.

We covered a couple more examples from §16.4 and proved the identity

We covered some of the examples in §16.5. We saw how to compute the mass of a two-dimensional domain (a ``plate'') with variable density, and also how to compute its center of mass. We also saw the definition of the moment of inertia of a plate (with variable density) rotating around a line or point. We evaluated some relevant double integrals.

HW Problems §16.5: 1-4, 11, 12, 14, 17, 25.

We saw briefly how triple integrals are defined (in a completely analogous way to double integrals, so we did not insist much on §16.6) and proceeded to evaluate some triple integrals by repeated integration.

HW Problems §16.7: 3-6, 11, 14-16, 21-22.

We showed how to compute a triple integral in cylindrical coordinates.

HW Problems §16.8: 1-8, 11, 12, 17, 18, 25, 26.

We introduced the spherical coordinate system and how to use it for evaluation

of triple integrals.

We saw several examples of how to transform the domain of integration from cartesian

to spherical coordinates and carry out the integration in spherical coordinates (the form

![]() becomes now

becomes now

![]() ).

).

HW Problems §16.9: 1-4, 9-14, 16, 19, 20, 24, 26, 27.

We saw the general procedure for evaluating a multiple (double or triple) integral

over a domain ![]() after first doing a change of variables. This is essentially

a way of parametrizing

after first doing a change of variables. This is essentially

a way of parametrizing ![]() using two or three variables (depending on the whether the

domain

using two or three variables (depending on the whether the

domain ![]() is in the plane or space) which run over a more convenient

domain

is in the plane or space) which run over a more convenient

domain ![]() . We say how to do this when

. We say how to do this when ![]() is a parallelogram (and we got a parametrization

with paramaters

is a parallelogram (and we got a parametrization

with paramaters ![]() and

and ![]() running through the rectangle

running through the rectangle

![]() )

and also in some other cases.

We also saw that the form

)

and also in some other cases.

We also saw that the form ![]() transforms into the form

transforms into the form

![]() (and similarly in three dimensions), where

(and similarly in three dimensions), where ![]() is the so-called

Jacobian determinant, which can be computed from the functions

is the so-called

Jacobian determinant, which can be computed from the functions ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

HW Problems §16.10: 1-2, 8-10, 12-14, 19, 20, 27, 29.

We defined the line integrals of a vector field

![]() along a curve

along a curve ![]() given parametrically by

given parametrically by ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

as the expression

,

as the expression

HW Problems §17.1: 1-4, 7, 15, 16, 20, 21, 23, 25, 28-30.

This says that if a vector field ![]() is a gradient field, then a line integral of that

along a curve

is a gradient field, then a line integral of that

along a curve ![]() equals the value of

equals the value of ![]() (where

(where

![]() ) equals

) equals

![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the endpoints of

are the endpoints of ![]() . This is true in two and three dimensions,

and, in two dimensions, in order to decide if

. This is true in two and three dimensions,

and, in two dimensions, in order to decide if ![]() is a gradient field we need to verify

that

is a gradient field we need to verify

that ![]() when the domain

when the domain ![]() , where

, where ![]() is defined, is simply connected (i.e. connected

and with no ``holes'').

is defined, is simply connected (i.e. connected

and with no ``holes'').

HW Problems §17.2: 1-4, 12, 13, 22, 24-26, 28.

My office hours tomorrow, April 12, will last only until 11am.

We discussed kinetic energy and why its change is due to the work is done by the force field on the particle. Also we talked about conservative (gradient) fields and the potential function.

HW Problems §17.3: 1-3, 6, 7, 8.

We saw an alternative way of writing the line integral

![]() as

as

![]() , where

, where

![]() .

We also saw the line integral w.r.t. arc-length, denoted by

.

We also saw the line integral w.r.t. arc-length, denoted by ![]() , where

, where

![]() is a scalar function.

is a scalar function.

HW Problems §17.4: 2, 3, 5, 17, 18, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 36.

We stated Green's theorem. This expresses a line integral along a closed curve as a double integral over the interior of that curve. We proved this in the case when the domain if of Type I and of Type II and showed how one proves this if the domain is more general by cutting up the domain into a finite number of non-overlapping parts each of which is of both Type I and II. We also explained how to parametrize the boundary of a domain if that is not simply connected or even not connected (walk along the boundary in such a way that the domain is always on your left).

HW Problems §17.5: 1, 2, 5, 6, 18-20, 26, 28, 30, 31.

We saw how to apply Green's formula to derive a formula for the area of a polygonal region

that has been described to us by the coordinates of its vertices. We also saw how to find an analogous

formula for the centroid of the polygon and for the volume

of the solid that arises if we rotate a polygonal region

(which is part of the right half plane

![]() ) about the

) about the ![]() -axis.

-axis.

We saw how to calculate the area of a surface which has been given to us in parametric form.

HW Problems §17.6: 1, 2, 5, 6, 15, 16, 17, 22, 23, 35, 36.

You may find it here in PDF.

I answered various questions of the students.

We went through the practice final exam that was distributed on Wednesday.

It will take place in Skiles 202 (lecture room), on Friday May 4, from 11:30 to 14:20.

We had our final exam. Here are the problems:

Hint: Use the normal vectors to ![]() and

and ![]() at

at ![]() .

.

Hint: Do not use Green's theorem.

You may find them here.

I will be in my office on Sunday May 6, from 6 to 7pm, in case somebody wants to see an exam paper. After that the grades will be finalized.

Mon May 7 20:15:18 EDT 2007: There had been an error in the software that computed your numerical scores, which had as an effect that the quizzes were not counted (and possibly other effects). This error has now been corrected (I hope) and your numerical grades are now correctly computed (please, check yours, and let me know if you believe there is a numerical error in your posted numerical grade).

Some letter grades have inevitably been changed as the landscape changed, most of them for the better I believe, but not all.

I will enter the corrected grades into the system tomorrow but the process is slow and the changes may not show up online for several days.

I apologize for this mistake. I wish one of you had checked the numbers concerning him/her but, amazingly, no one did (at least, no one notified me of the discrepancy). Neither did I until today when I realized the error.